Technical Brief

Introduction

In 2022, facing a free-falling currency and dwindling foreign reserves, Ghana’s policymakers turned to an unorthodox lifeline: gold. The Bank of Ghana launched a Gold-for-Reserves (G4R) program to leverage the country’s gold output for macroeconomic stability[1].

What made the Ghanaian adoption of an age-old idea interesting was the degree of desperation and how that drove the scale of the program rapidly and massively. Whereas it took countries like Bolivia 4 years to reach 174 kilograms of gold in a similar program, Ghana was soon doing tons of the metal in bare months.

The idea is simple enough: use cedis to buy domestic gold, then swap or sell that gold for foreign exchange. This would bolster the central bank’s reserves and ease pressure on the Ghanaian cedi[2], all while formalizing more of the small-scale gold trade. By late 2025, four years after the idea was first broached, officials hailed the program for lifting Ghana’s reserves from near-critical lows (barely two weeks of import cover at the end of February 2023) to several months’ worth[3]. The cedi’s precipitous decline slowed, and confidence crept back into the economy. In short, gold was hoisted as the strategic instrument in Ghana’s fight for currency stability and fiscal breathing room.

Yet this golden intervention was only one among several others, and it came with a significant cost. Stabilizing the cedi via gold purchases required financial trade-offs, as the central bank absorbed various losses to keep the system running. As one IMF review noted, the G4R initiative had, by September 2025, racked up about $214 million in provisional losses, roughly 0.2% of GDP[4]. The Bank of Ghana effectively chose to bear these costs in exchange for shoring up the currency, knowing very well that gold inflows constituted only one part of the turnaround story.

“The gold initiative… played a vital role in that stabilization effort, though it came at a cost,” Governor Johnson Asiama acknowledged[1]. The policy logic has now been repeated non-stop: sacrifice some fiscal and balance-sheet comfort to achieve currency and economic stability in a time of crisis.

Now, with the acute crisis past, attention must urgently turn to how to determine the precise contribution of the program to the Cedi’s performance and in that clear-eyed manner ascertain therefore the right level of costs or losses, whichever terminology one fancies, the country must reasonably bear to keep the program running.

In exploring how the program can be refined to sustain the gains without bleeding public funds, a series of critical questions emerge: how much intervention by the central bank in the forex (FX) market is reasonable, what level of exchange rate should the central bank try to use intervention to maintain, and how much gold then should it demand from the GoldBod aggregation mechanism? Those questions underline the predicate question of how much losses the country should tolerate, if any at all.

But what if the program could do away with the losses without completely sacrificing the strategic options of intervention available to the central bank? How important answering that question obviously also depends on how worse the losses can get and under what scenarios, the entire program becomes a net negative.

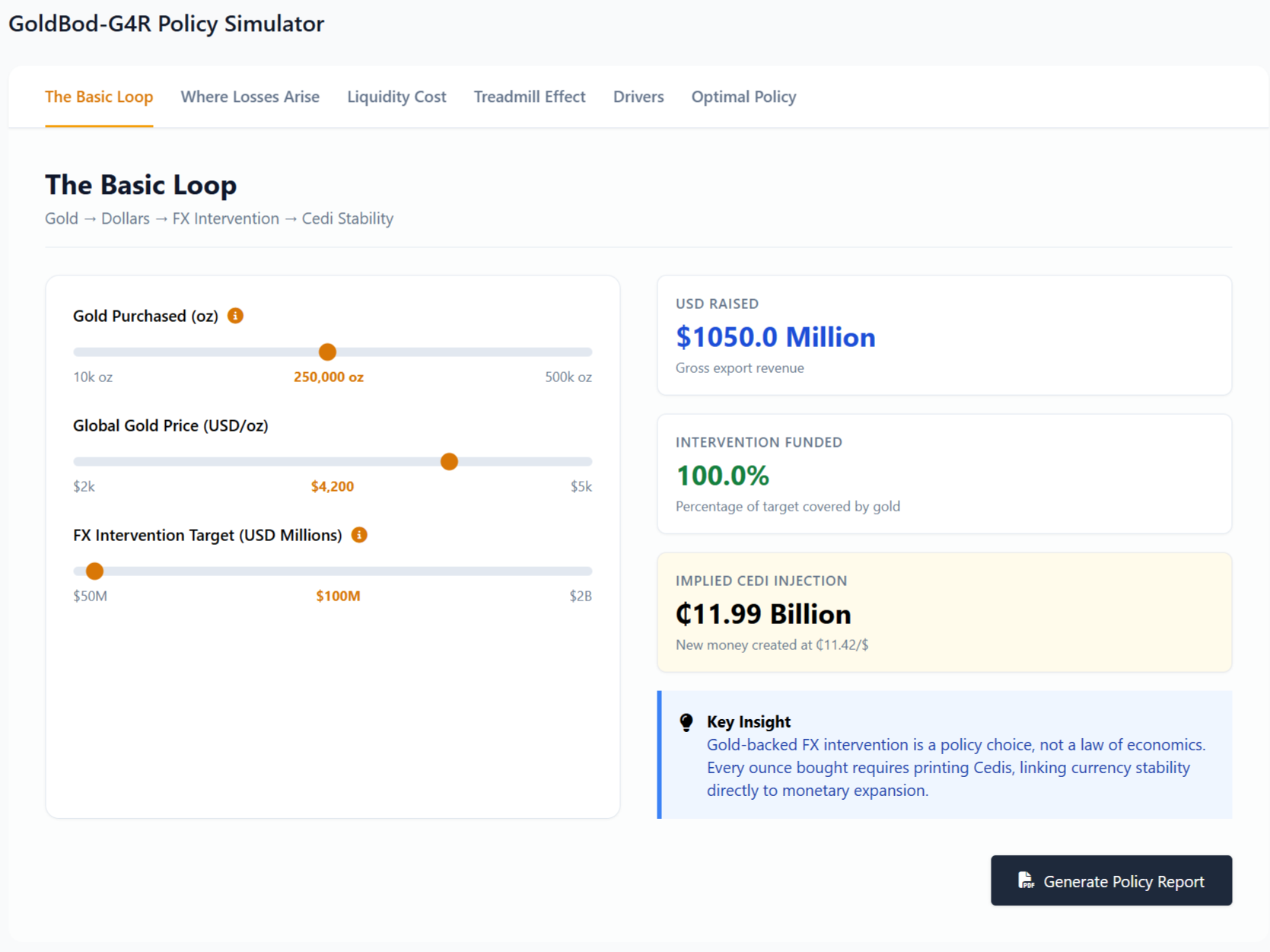

This short brief does not seek to answer every one of the above questions in detail. What it does, however, is enrich the understanding of those readers who, having used the dashboard on the simulator page, now wish to go forward and dig deeper into the trade-offs, tensions, and challenges, and explore possible solutions.

Inside the GoldBod Model: Aggregators, Off-Takers, and Incentives

At the heart of Ghana’s gold-for-reserves program is a new institution, the Ghana Gold Board, nicknamed GoldBod. Established in 2025, GoldBod serves as the sole authorized buyer and trader of gold for the state[5]. Its mandate is sweeping: buy gold from domestic sources (large mines and small-scale miners alike), assay and refine it as needed, and then channel it either into the central bank’s reserves or to strategic trades (such as swapping gold for fuel or foreign cash). In practice, GoldBod operates through a network of licensed players: gold aggregators, small-scale mining dealers, and foreign off-takers. Understanding these roles is key to grasping the program’s mechanics – and its pitfalls.

Aggregators are middlemen who gather gold, especially from Ghana’s thriving artisanal and small-scale mining sector. Under the Gold-for-Reserves (G4R) program, GoldBod approves certain aggregators (including former Precious Minerals Marketing Company agents) to buy dore gold (unrefined gold bars) from miners on its behalf[6]. In the current design, only a single aggregator has been licensed and granted a special role with financing from the central bank to kick-start purchases. Armed with interest-free cedi advances, this top aggregator can pay miners promptly - even offering a small bonus above prevailing market price to entice sellers[7].

These incentives were meant to draw gold out of the shadows (and away from smugglers), into official channels. GoldBod’s CEO openly conceded that “the program intentionally uses realistic market incentives” - i.e. higher prices - to secure miner participation[8]. The strategy has definitely worked in boosting volumes: by one account, Bank of Ghana purchased roughly 3.6 million ounces (over 100 tons) of gold in local currency between 2021 and 2023[9]. In 2025 alone, the GoldBod reports purchases of roughly 103 tons of gold, with some experts suggesting that a trend of reverse smuggling has set in and the GoldBod is now attracting smuggled gold from the sub-region into Ghana and thus subsidising inbound smugglers, who would ultimately take their money in the form of FX outside the country.

But there is a catch. Relying on a single, bank-funded “super-aggregator” to dominate purchases created structural inefficiencies. Smaller gold buyers couldn’t outbid an aggregator backed by the central bank’s deep pockets[7], so competition in the supply chain literally evaporated. The GoldBod suggests that competition is not desirable anyway. But to the extent that gold is a finite and scarce resource, and multiple traders are after it, competition should be inevitable in a well-functioning market.

At any rate, with weak competition and over-concentration, GoldBod effectively became a monopsony (sole buyer) in the small-scale gold market. This structure, while expedient, sowed the seeds of cost escalation and opacity. The main aggregator passed the generous pricing (the miner bonus) down the chain, guaranteeing miners a premium that the government ultimately funded. It was a public subsidy in all but name. One that would have to be recouped (or recorded as a loss) when the gold was finally sold abroad.

Off-takers are the flip side of the equation. They are the buyers at the end of GoldBod’s chain. These are typically international gold refiners or traders who provide foreign currency (or critical goods like fuel) in exchange for Ghana’s gold exports. Presently, Ghana leans on a handful of such partners in the Middle East and South Asia. India and the UAE accounts for 99% of purchases in most recent quarters. In fact, just 3 - 4 firms in Dubai and India have accounted for the bulk of the gold off-take[10]. To move large volumes quickly and meet BoG’s reserve and FX intervention liquidity targets, deals were struck at slight discounts to world market prices, effectively granting off-takers a margin. Additionally, because much of the gold came as doré from myriad small producers, assay and refining adjustments were needed - typically a 0.5 - 1% penalty for purity and processing. Logistics and insurance added further basis points of cost.

All told, by the time GoldBod paid the miners and aggregators and then shipped and sold the gold, a net loss per ounce was virtually built-in. The program’s designers understood this: they were trading some “commercial performance” for policy gains[11]. One analysis calculated that with typical settings (e.g. a 1.5% miner bonus, ~1.5 to 2% combined off-taker discount and assay costs), the state loses roughly 4% of the gold’s value on each round-trip – a subsidy to keep the pipeline flowing. These are the “operational costs” GoldBod now says it accepts that it must minimise[8].

Compounding the trading losses is a monetary side effect. Every ounce of gold GoldBod buys injects liquidity into the economy: cedis are paid out to miners and dealers. To prevent inflation or exchange rate overshooting from this surge in local currency, the central bank engages in sterilization. It essentially mops up the extra cedis by selling bonds or other instruments. Sterilization carries a steep interest cost, especially in Ghana’s high-rate environment (policy rates have hovered in the 20 - 30% range until more recently when it slumped to the 15% to 20% range).

For example, financing GHS 1.14 billion (≈$100 million) of gold purchases for a year at a 22% policy rate would rack up about GHS 251 million in interest (~$22 million)[12][13]. Thus, even if gold trades were perfectly breakeven, the act of intervening in the currency market via local money creation imposes a fiscal cost. In reality, both trading losses and sterilization costs have been adding to the bill. It’s no surprise the IMF flags G4R as a “quasi-fiscal” operation. What they are effectively saying is that the government is spending a significant subsidy to prop up the cedi[14].

Not explicitly highlighted by the IMF but important all the same is the realisation that Ghana has been moving from a “managed float” approach to managing the exchange rate to a more rigid “managed peg” model, whereby “inflation targeting” has been supplemented by the politically sensitive task of “exchange rate anchoring” as the prime mandates of the central bank.

To demystify these dynamics, the interactive dashboard immediately below allows readers to experiment with Ghana’s Gold-for-Reserves model. Adjust the parameters to see how policy choices impact outcomes: miner bonus, assay loss, off-taker discount, and sterilization rate. For instance, try raising the “Miner Bonus” slider. You would see GoldBod’s purchase price per ounce climb above market, which increases the “loss per ounce” metric. In turn, the “loss per $ of FX earned” will tick up, indicating a less efficient conversion of cedi to reserves. Now lower the bonus to zero – the cost gap narrows, but consider what that might mean for miner participation. Next, tweak the “Assay/Purity Loss” setting. A higher percentage here mimics a scenario of poorer quality gold or assay disputes, which reduce the export value of each ounce. The widget shows how even a 1 -2% assay shortfall can shave millions off receipts when volumes are large. Similarly, increase the “Off-taker Discount” to see the effect of giving foreign buyers a better deal: the central bank’s loss per ounce grows, while the share of the FX target met might rise if that discount was what clinched higher volumes. Finally, experiment with the “Sterilization (Policy Rate)” parameter or the amount of cedi intervention. A higher rate means the central bank pays more to neutralize excess liquidity, which adds to the overall fiscal cost of the program (reflected in the interest cost output).

The Currency-Stability Trade-off: Intervention vs. Loss Control

Ghana’s gold program presents a classic policy dilemma. On one hand, the more aggressively authorities intervene as a matter of policy - buying up more gold, paying higher premiums, and flooding the market with cedi liquidity - the more they can bolster reserves and dampen exchange rate volatility, scoring a visible political goal of a stable currency. Indeed, G4R’s defenders credit it for the relative calm in the cedi during 2023 - 25 compared to the freefall of 2022[15]. By intervening, the central bank essentially outbid private forex buyers for gold, ensuring those dollars (from eventual gold exports) went into the public coffers to back the cedi[9][16]. Supporters argue that without this program, much of that gold might have been smuggled or sold abroad with proceeds never repatriated, worsening the FX crunch[17]. In that sense, the intervention is presented as having achieved its primary goal: improving currency stability and reserve levels when Ghana needed it most.

On the other hand, every intervention had to be “paid for” with public resources. High bonuses or “competitive prices” for miners meant the central bank willingly buying gold at above-market rates – effectively a transfer to gold producers. Off-taker discounts and refining costs meant the bank sold below full value, leaving money on the table to accelerate deals. And the cedi liquidity expansion meant higher interest payments on the BoG’s sterilization bonds[18][19]. These have been cast as deliberate policy choices: Ghana chose to absorb short-term losses and risks onto the public balance sheet in hopes of a larger macroeconomic payoff. Officials justify this as the price of averting an even deeper currency crisis. “This is the price one pays for diverting small-scale gold dollars from commercial banks to the government,” one analyst noted of the strategy[16]. The Ghanaian public, by and large, supported the idea - after all, Ghana is Africa’s top gold producer, yet until recently the state’s gold metal reserves were negligible[20]. If the country’s patrimony could be harnessed to stabilize the economy, many felt it was worth a try, costs and all[21].

Now, however, with the immediate crisis abating, scrutiny of those costs has intensified. Ghana’s gold stabilization program is moving from emergency mode to long-term mode, and questions of efficiency and equity loom large. How much should the central bank (and by extension the taxpayer) keep subsidizing these gold trades? Can the same stabilizing effect be achieved with less of a hit to the public purse? Can a challenge be set to strike a sustainable balance on the intervention-loss spectrum? Even GoldBod’s management concedes that while losses were “unavoidable” in the program’s first phase, they must be reined in as the model matures[8].

In short, even by the measures of the program’s strongest proponents, Ghana is now reassessing the trade-off: how to keep the cedi stable without treating the gold program as a blank check.

For now, we do not intend to re-litigate the issues of the relative contribution of gold-dollars mobilised through the GoldBod channel to the Cedi’s performance against the dollar over the period. Suffice it to say that, elsewhere, we have questioned the theory of a dominant contribution. In the same vein, we will not flog the issue of whether the GoldBod’s model is a sustainable economic response to smuggling. We have argued on national television that smugglers are incentivised by income tax evasion benefits that dwarf any pricing margins that GoldBod might offer. In the rest of this short paper, we simply take the supportive arguments of GoldBod’s and G4R’s champions at face value.

Structural Inefficiencies: Are Losses Inevitable?

One critical insight from the past two years is that G4R’s losses were not a fluke of bad luck, or market volatility. Rather, they were baked into the structure. Losses based on market volatility are additive.

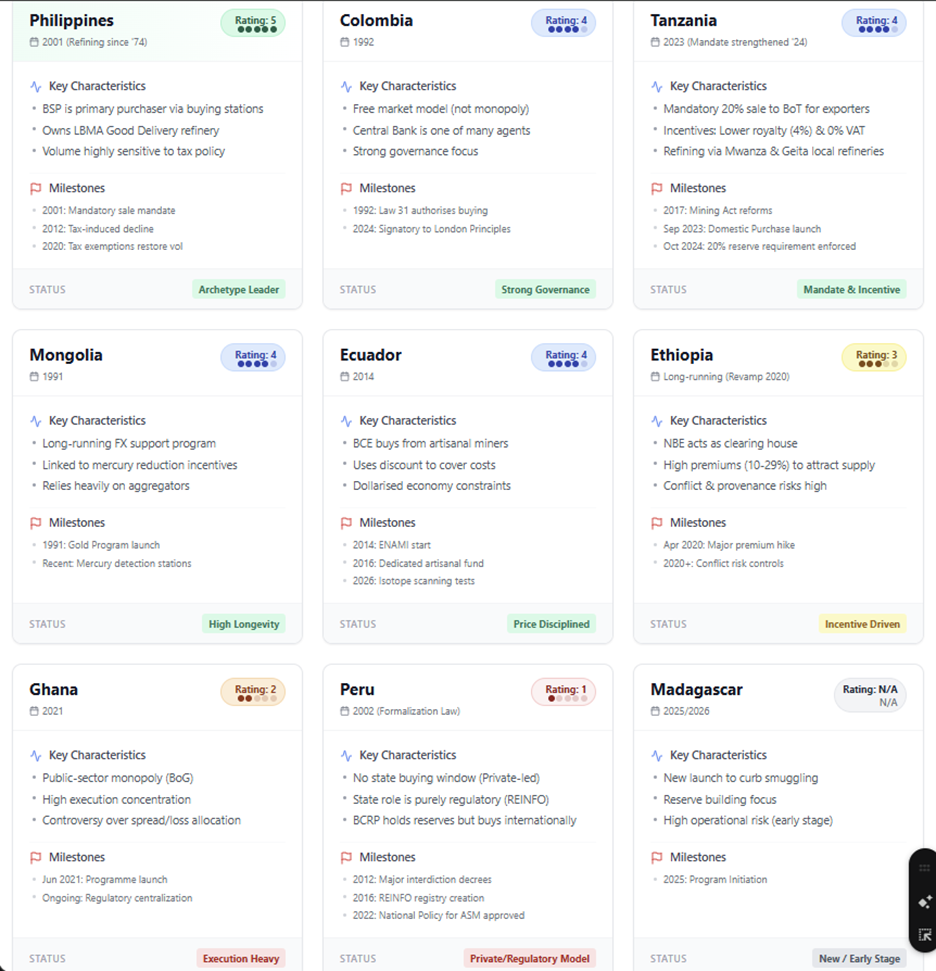

The program’s architecture concentrated too much power in a few hands and relied on non-market pricing for the sake of speed. This means the losses, while real, are also potentially addressable design flaws, not intrinsic to any gold-for-FX scheme (recall the earlier comparative analysis of Gold-for-FX/Reserves programs in 7 other countries). As the IMF has stressed, the central bank’s gold operations amount to quasi-fiscal activities, a telling term that implies these are policy-induced costs, not random market outcomes[14]. In other words, the state “chose” these losses by the way it designed the intervention. And that is good news in a sense: better design can likely eliminate a good portion of the inefficiencies.

What were these structural inefficiencies? First, the near-monopoly aggregator model removed competitive pressure that might have driven down costs. With one big player (and its hand effectively in the public till), there was little incentive to minimize the gap between buy and sell prices. GoldBod’s heavy influence meant prices paid to miners were set administratively (to meet policy goals) rather than through open market competition.

Second, the opacity and concentration in off-takers - dealing with just a few foreign buyers - put Ghana in a weak negotiating position. Off-takers knew the government needed to offload gold regularly to meet reserve targets, which likely strengthened their hand in demanding discounts or favorable terms. This too was a structural choice: by partnering with a small cadre of buyers, the program may have forfeited the chance to get better prices via broader auctions or diverse markets.

Third, all the market risk was sitting with the central bank. Gold price swings, currency movements, assay uncertainties, everything. GoldBod simply charges its fees, pockets the proceeds, and stands by whilst the risks are offloaded to the central bank, masked as “operational losses”. Private intermediaries, by contrast, operated on fixed margins with no skin in the game beyond their narrow role[19][22]. For instance, licensed gold buyers (aggregators) did not suffer if world gold prices dipped after BoG purchased; that risk was BoG’s. As the Chamber of Gold Buyers pointed out in response to the IMF’s report, the losses “sit on the books of the Bank of Ghana,” while aggregators and buyers “neither profit from nor absorb losses” due to price movements[23]. This one-sided risk absorption is a recipe for moral hazard and inefficiency.

Luckily, losses are not inevitable if these inefficiencies are addressed. Ghana’s program is actually late to the game - other gold-producing countries like Turkey and the Philippines have run domestic gold purchase schemes with far less drama[24]. The difference often comes down to design features. For example, Turkey uses gold-backed bonds and monetization schemes that mobilize private gold holdings with the central bank as a facilitator, not a direct counterparty, thereby sharing the financial burden with banks and investors[25]. The Philippines’ central bank buys gold from small-scale miners at a slight discount (to cover refining costs) but has a tax-exempt structure to make it worthwhile for miners, avoiding heavy bonuses. Ecuador, cited by analysts, adopted pricing formulas to minimize losses when it briefly tried a similar program[24]. These international experiences suggest that Ghana can recalibrate G4R to reduce - or even eliminate - the structural losses without necessarily abandoning the goal of currency stability. It requires shifting from an emergency, centralized model to a more market-driven, transparent framework.

The “Trust-Chain” Model: A Path to Smarter Gold Mobilization

Emerging from these debates is a reform blueprint dubbed the “Trust-Chain” model. This concept reimagines the gold-for-reserves program as a transparent, market-based network rather than a single pipeline dominated by the central bank. The core idea is to reconfigure the gold aggregation-financing-trading nexus so that risks and rewards are distributed to those best positioned to handle them - the market - instead of loading all risks onto the public sector.

How would the Trust-Chain work? First, GoldBod’s role would transition from principal trader to regulator and facilitator[26]. Rather than handing one company cheap funds to buy gold, GoldBod would certify and oversee a competitive network of aggregators. Multiple aggregators, including those self-financed or backed by private capital, could bid to purchase gold from miners, competing on price and efficiency. This immediately injects competition at the source, likely narrowing the gap between what miners get and what the global market will pay. No more one-size-fits-all premium set by the state; instead, market forces determine a fair price (with perhaps a modest floor to ensure small miners still get a decent deal). GoldBod ensures all aggregators meet strict due diligence (to prevent sourcing from conflict or illicit mining) and maintains a real-time ledger - a “trust-chain” - of all gold flows. Modern tech like blockchain or digital assays could be leveraged to trace each ounce from mine to vault, building confidence in purity and provenance, but such specific technologies are not indispensable. Any sound Enterprise Resource Platform (ERP) would do. This “integrated value chain” model fosters trust among all players, hence the “Trust-Chain” moniker.

Second, financing for gold purchases would shift to the private sector or semi-private funds. One proposal is to establish a Gold Reserve Fund co-financed by the central bank, sovereign funds, and private investors[25]. This fund (or others, like commercial bank credit lines) would provide working capital to aggregators at commercial rates, not free money. That means if an aggregator wants to buy up, say, $50 million of gold, they might borrow from this fund or issue a gold-backed bond, paying interest or giving up a share of profits. The cost of capital is now on the aggregators’ books, not the central bank’s, aligning incentives for efficiency. They won’t overpay for gold or sit on inventory too long, because it’s their interest expense accruing. The Bank of Ghana could still backstop certain extreme risks (for example, acting as a buyer of last resort if prices crash), but it would not be fronting all the cash for day-to-day operations. By letting market players skin-in-the-game, the system naturally curbs the subsidy problem.

Third, the off-take side would be liberalized and broadened. Instead of a cozy arrangement with a few off-takers in Dubai or Mumbai, Ghana could open up its gold exports through competitive auctions or diverse channels. In fact, the Bank of Ghana recently piloted a gold FX auction platform to sell portions of gold for dollars more transparently[27]. A Trust-Chain network would build on this: certified exporters or GoldBod itself could auction gold to the highest bidders internationally, or even develop a domestic “gold for FX” bourse where local banks and international traders bid for gold using hard currency. This would replace the fixed off-taker discounts with market pricing, ensuring Ghana gets the best possible price at each sale (minus standard fees). It also reduces reliance on any single buyer or country, spreading Ghana’s market reach. If one off-taker offers a lowball price, another will outbid if demand is there. The outcome is better pricing and no need for BoG to concede large discounts to guarantee a sale.

Finally, risk management and transparency would anchor the entire chain. Each step, from aggregator purchase to final export, would have clear, published pricing benchmarks (like LBMA gold price references) and defined fees[28]. Hedging tools could be employed: for instance, GoldBod or aggregators might use forward contracts or options to lock in prices, so they’re less exposed to swings during the logistics and refining period[29]. Explicit risk-sharing agreements would specify who bears the cost if, say, purity comes in lower than expected or if gold prices drop between purchase and sale. Rather than silently booking a loss on BoG’s balance sheet, such events could be absorbed by the private fund (up to a point) or insured against. Crucially, regular audits and public reports would be part of the model, to keep all players honest[30][28]. This would help “shine a light” on a process previously criticized for opacity[31], building public trust that the nation’s gold is being managed prudently.

In essence, the Trust-Chain model aims to preserve the benefits of Ghana’s gold program – contributing to reserves accumulation that supports currency stability, and formalization of small-scale mining. All the while eliminating the inefficiencies stemming from state-dominated trading. By moving GoldBod “upstream” into a governance and oversight role, and empowering the market to handle trading under transparent rules, the government can still achieve its objectives without directly footing the entire bill. As one policy analyst put it, Ghana needs to ensure “sustainability does not rest on the Bank of Ghana alone”[32]. The Trust-Chain would do exactly that: make currency stabilization via gold a shared responsibility of the central bank, finance ministry, private investors, and the mining community – rather than a costly solo venture.

It goes without saying that such a model would only be viable if the Bank of Ghana is not desperately suctioning all the gold in Ghana in a relentless intervention spree to fix the currency at an unrealistic level. Smart modelling is required to better and transparently anchor the right currency fluctuation band (responsive to market conditions), the rational degree of intervention, and the consequentially appropriate volume of gold-dollars the supply of which the central bank must backstop to meet policy goals.

Conclusion: Toward Sustainable Resource Mobilization

Ghana’s experiment with Gold-for-Reserves has been nothing short of remarkable. It showed that even in the throes of crisis, innovation in domestic resource mobilization can be scaled up. Using gold to stabilize a currency - a throwback to the gold standard, in some respects - has seized the imagination of the policy community. But it has also taught a timeless lesson: bold solutions must be matched with sound design. The initial G4R framework, while spunky, carried avoidable inefficiencies that threatened to undercut its long-term viability. The Bank of Ghana itself admits that at least one component of the strategy, the Gold-for-Oil program, was so problematic it had to be terminated outright. Since it was killed, there has been no effect on prices at the pump.

The simulation dashboard accompanying this analysis makes clear that Ghana need not accept perpetual losses as the price of currency stability. By embracing reforms like the Trust-Chain model - which realign incentives, introduce competition, and increase transparency - Ghana can almost have its cake and eat it: a steadier currency and a cost-effective, equitable gold program. Such scenario modelling, made easy to intuitively grasp through digital tools, should become an essential part of the toolkit to defeat a major source of the katanomic malaise facing countries in Ghana: analysis-fatigue among prospective policy audiences.

The stakes, without doubt, go beyond one country. Many commodity-rich nations struggle with the paradox Ghana faced: considerable natural wealth alongside fiscal and foreign exchange fragility. The path Ghana is forging - converting natural resources directly into financial stability - is an enticing one, but it must be trod carefully. Strong institutions, accountable governance, and smart risk-sharing are the pillars of any durable resource mobilization strategy. In simple terms, these are policy-intensive domains easily swamped and overshadowed by political gamesmanship and posturing about resource-nationalism. Such that even faced with clear underperformance and negative results, some continue to cling to bad ideas out of affective pride. That is precisely how katanomics thrives in otherwise vibrant democracies where course-correction through national learning should be the norm.

In charting a course to refine its Gold-for-Reserves program, Ghana has the opportunity to set a powerful example. It can demonstrate how a developing country, through ingenuity and reform, turned a quick fix into a permanent feature of economic resilience. Done right, the model could become a blueprint for others. The path could be lighted as to how to leverage natural resources for national stability without succumbing to the pitfalls of opacity or unsustainable costs [1][33]. With prudent reforms and an unwavering commitment to transparency, Ghana can strike gold in more ways than one. By securing more than just reserves, the country’s leaders can build trust and wealth for generations to come.

General Note on Sources: Public statements and reports from Bank of Ghana and IMF; policy analyses by independent economists and media. The interactive widget is based on a model of GoldBod’s operations (parameters from recent Ghana Gold Board data and IMF reviews). All figures are for illustrative purposes.

References

[1] [27] [32] Ghana to Broaden Oversight of Gold-Backed Stabilization Scheme as Economy Moves Beyond Crisis

https://thehighstreetjournal.com/bog-gold-backed-stabilization-scheme/[2] [6] Responsible Gold Sourcing Policy Framework – Bank of Ghana

https://www.bog.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Responsible-Gold-Sourcing-Policy-Framework.pdf[3] How Ghana’s Central Bank is Helping the Economy Recover – IMF

https://www.imf.org/en/news/articles/2025/12/04/how-ghanas-central-bank-is-helping-the-economy-recover[4] [18] [19] [22] [23] [29] US$214m Gold Loss: Gold Buyers Push Back on IMF Claims

https://www.modernghana.com/news/1460256/us214m-gold-loss-gold-buyers-push-back-on-imf.html[5] [8] GoldBod Plans to Streamline G4R Programme – Ghana Gold Board

https://goldbod.gov.gh/goldbod-plans-to-streamline-g4r-programme-reduce-costs-while-maintaining-economic-gains/[7] [10] [24] [26] Post by Bright Simons on LinkedIn

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/bright-simons-1390432_1-on-saturday-last-i-appeared-on-a-show-activity-7413963207771463680-f8MU[9] [15] [17] [31] From Gold-4-Oil to GoldBod; Can You Trust the Process? – The Scarab

https://brightsimons.com/2025/01/from-gold-4-oil-to-goldbod-can-you-trust-the-process/[11] [14] [16] [20] [21] Is the IMF Lying About Ghana's GoldBod? – The Scarab

https://brightsimons.com/2025/12/is-the-imf-lying-about-ghanas-goldbod/[25] [28] [30] [33] Refining Ghana’s Gold Strategy: A Policy Workshop

https://www.modernghana.com/news/1461773/refining-ghanas-gold-strategy-a-policy-workshop.html